“Of what use is a philosopher who doesn’t hurt anybody’s feelings?”

― Diogenes of Sinope

“I do not ask the wounded person how he feels, I myself become the wounded person.”

― Walt Whitman, Song of Myself

“Starcraft involves Soulcraft”

― Michael Sandel

During its enduring two-century death struggle, philosophy has grown increasingly self-conscious. In the German language, this word carries connotations of self-assuredness, while in English, it implies precisely the opposite – a diminished sense of self-confidence. If philosophy were a person, ‘he’ would be like a lost man in a basket of deplorables, still pursuing an ideal of greatness, all the while harboring a fear that this ideal may have never truly existed. This erosion of confidence initiated two centuries ago during his marital war with science. In a marriage with a progressively distant partner, his erstwhile distinction as the universal lover of all things became a futile notion. Once entrapped by the allure of grand romantic ideals, a commitment that had persisted since the era of Aristotle, he now found himself in a union where love, once an emblem of his grandeur, had degenerated into an impractical fantasy. After millennia of devotion, the overqualified lover confronted a stark reality—he was ill-suited to sustain a marriage of convenience. In truth, he could never erect the sturdy foundation he had pledged to provide for his spouse. With God, the guardian of unity, receding, science moved out to become an independent woman. By the mid-19th century, philosophy lost not just his intellectual foundation but also his sense of home and occupation, leaving him to stand on the streets as a metaphysically homeless man grappling with an existential crisis.

In the midst of this chaos, the uninvited offspring of philosophy and science, each a staunch relativist in their own right, reveled amidst the wreckage of what Dilthey had termed “the fallen systems.” Just like a desolate father grappling with a midlife crisis, he found himself incapable of curbing the rampant “anything goes” mindset of these wayward children.

A century had elapsed, marked by the shifting masquerades of fascism and postmodernism, where themes like nationalism, existentialism, pessimism, nihilism, communism, post-communism, post-modernity, and post-postism wore their colorful but divisive costumes. These relentless skirmishes against the patriarch had taken their toll.

In a final attempt at convalescence, he embarked on a journey to America. Philosophy sought to salvage itself and committed to a regimen of speech and communication therapy. Having lost his psychologist friends to his estranged partner, it seemed like one of the last remaining lifelines. Yet, the fractured self, wounded at its core, proved beyond mending.

As the curtain drew on the last century, his exposed and festering wounds brought him to the precipice of mortality. Despite numerous resuscitation efforts, Sloterdijk thus reflects on the fading existence of the aging, white Western man:

For a century now philosophy has been lying on its deathbed, but it cannot die because it has not fulfilled its task. Its farewell thus has been tortuously drawn out. Where it has not foundered in the mere administration of thoughts, it plods on in glittering agony, realizing what it forgot to say during its lifetime. Faced with its demise, it would like now to be honest and reveal its last secret. It confesses: The great themes, they were evasions and half-truths. Those futile, beautiful, soaring flights—God, Universe, Theory, Praxis, Subject, Object, Body, Spirit, Meaning, Nothingness — all that is nothing. They are nouns for young people, for outsiders, clerics, sociologists (Sloterdijk, Critique of Cynical Reason xxvi ).

Now, amid the poignant acknowledgment of his less fortunate circumstances, traces of pride still linger. The years have advanced, yet the vestiges of past privileges continue to sustain him. The university, now his refuge, stands as a sort of senior residence for a man whose body may falter, but his cherished memories remain steadfast.

Here, the professors assume the roles of welcomed therapists. Much like vigilant physicians, they monitor the machines that serve as his lifelines, provide companionship during moments of despair, and offer diversions from the inevitable approach of life’s final transition. However, the stark reality remains unmasked—he is an elderly, white Western man, someone who few genuinely wish to visit, not even on the occasion of Christmas.

Already in 2015, Japan cut down its liberal arts programs. The then-Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, articulated his vision, stating, “rather than deepening academic research that is highly theoretical, we will conduct more practical vocational education that better anticipates the needs of society”. Across the ocean in the United States, some foresee an impending higher ed “Apocalypse” by 2026. Enrollments in liberal arts have already dwindled, prompting certain commentators to lament the presumed doom of liberal arts colleges (Link):

Because of low birthrates following the Great Recession […] the four-year-college applicant pool is likely to shrink by almost 280,000 per class, over four years, starting in 2026, a year known in higher ed as “the Apocalypse. (Are liberal arts colleges doomed)

Shouldn’t we consider the compassionate act of removing his life-support and sparing him further agony? When a horse sustains a broken leg, it is often put down, but the question arises: when is the right time to put an end to a philosopher’s suffering? At least, we could say: “Philosophy is dead, and we have killed him”.

“We killed philosophy, all of us, by treating it as a discipline among others, by becoming professionals who sell philosophy, by becoming experts, by building resumes, identities and marketing ourselves to be paid, be branded, by writing books, by publishing articles that are written for making us promoted, by attending ‘conferences’ similar to other professional organizations, by making a career in philosophy.”

– Ferit Güven , ApaOnline

It appears that there are only two approaches to advocating for philosophy:

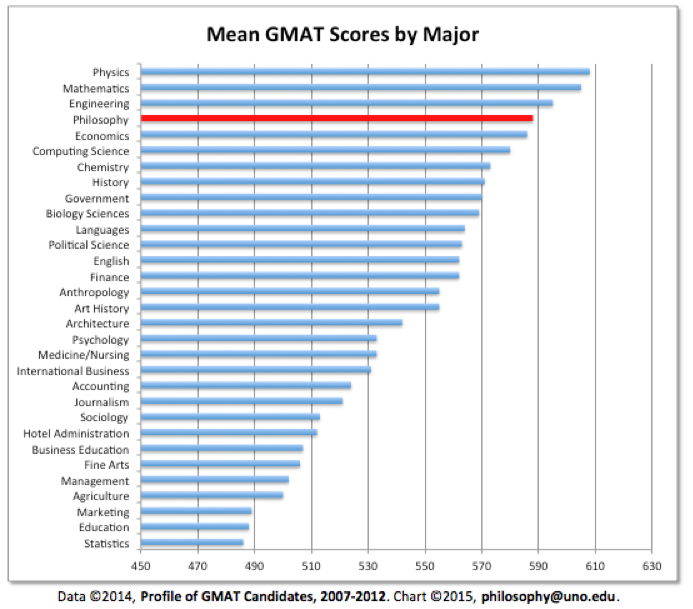

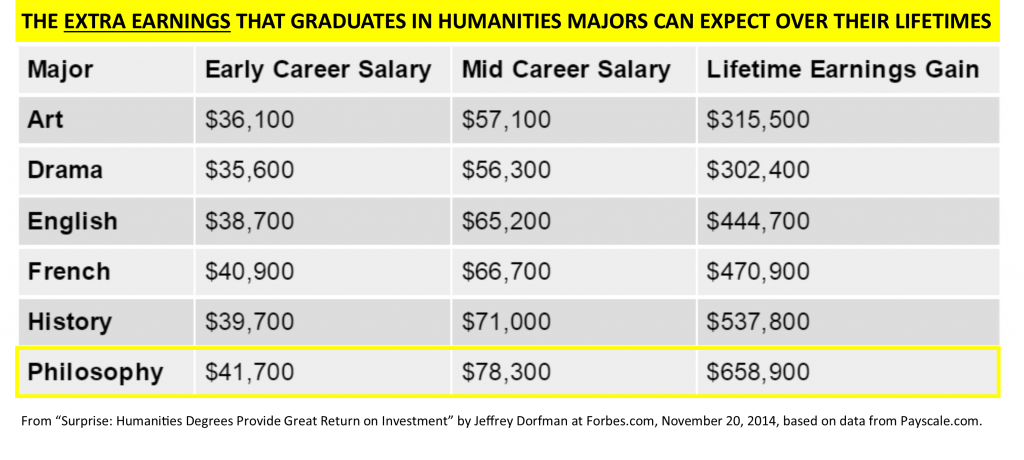

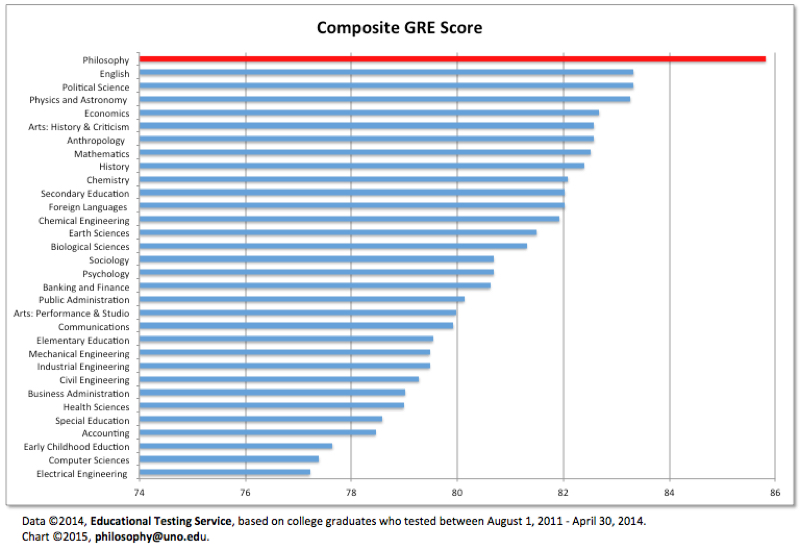

We can either assert that philosophy enhances students’ education and support our claim with compelling statistics and graphs showcasing the exceptional achievements of philosophy students

Statistics from: DailyNous

On the contrary, countering these arguments that bolster the external professional image of philosophy, we might contend that philosophy should remain detached from the economic discourse entirely. Such an association risks altering the intrinsically non-utilitarian essence of philosophy. As put forth by Güven, philosophy defies reduction to mere propositions; it exists as an unquantifiable discipline.

Nonetheless, Güven’s arguments liberate the philosopher from the need to continually justify their place within the university and society. As tuition fees soar to as much as 70,000 Dollars a year, we must pause to question: Can we genuinely endorse an excessively expensive major based solely on the vague promise of providing students with a warm, albeit nebulous, sentiment?

Maybe, we should ask instead what does it mean when somebody constantly remarks that he is important?

Socrates: Have you noticed on our journey how often the citizens of this new land remind each other it is a free country?

Plato: I have, and think it odd they do this.

Socrates: How so, Plato?

Plato: It is like reminding a baker he is a baker, or a sculptor he is a sculptor.

Socrates: You mean to say if someone is convinced of their trade, they have no need to be reminded.

Plato: That is correct.

Socrates: I agree. If these citizens were convinced of their freedom, they would not need reminders.”

― E.A. Bucchianeri, Brushstrokes of a Gadfly,

Similar to an elderly individual nearing the end of their life, numerous professors persistently underscore their significance. Perhaps these dialogues emerge from the necessity of philosophers to affirm their own vitality. In reality, however, such discussions might inadvertently cripple philosophy, squandering energy that could have been better invested in exploring philosophy’s true meaning.

Is there another way?

Rather than contributing to a protracted struggle that only extends the agony of philosophy while stoking his pride, we could adopt a more aggressive approach—punching, choking, and stabbing philosophy. Instead of standing idly by the bedside of the ailing, we could genuinely endeavor to bring about his demise. At the very least, we should refrain from sympathizing with his solitude.

The house that philosophy once erected now belongs to his ex-wife. In light of his unwelcome status, should he even consider revisiting this house? The endeavor may not result in any genuine loss, for the foundation of the house is inherently unstable. After all, what use does a philosopher have for a house?

Philosophy’s endeavor to dismantle itself could be seen as an acknowledgment of its authentic essence, constructed through relentless self-critique and energized by a yearning for deconstruction. Within this process, it has the potential to identify elements of itself that remain impervious to destruction.

We might even frame the challenge of self-annihilation through a more postmodernist lens: Does the very act of attempting self-destruction paradoxically undermine the concept of destruction itself? While it may appear that I advocate for a revival of Critical Theory, picturing ourselves on a path to transcend all narratives, contradictions, and institutions, as Helmut Schmidt aptly noted:

“People with visions should go to the doctor.”

Through uncritical destruction, philosophy risks far more than just the shackles it aims to break. Isn’t it a fact that our era has spawned a surplus of “critical” thinkers? With Critical Thinking becoming a fixture in mainstream discourse, textbooks emphasize the cultivation of critical thinking skills among students. A crucial facet of this practice involves the constant inquiry into the purpose behind any document.

Nonetheless, within the realm of the internet, virtually everyone appears to have acquired their share of critical thinking, with it becoming a pervasive attitude. The most intriguing examples of overconfident critics are undoubtedly the flat-earthers. They wage their solitary campaign against what they perceive as a deluded, Disney-influenced globalist majority, and their endeavors yield strange results. Take, for instance, the case of a “US daredevil” who endeavored to substantiate the notion that the Earth is flat and met his end in a homemade rocket crash. Even before his demise, he served as a reminder of our collective critical duties:

“I just want people to question everything. Question what your congressman is doing, your city council. Question what really happened during the Civil War. What happened during 9/11.”

Critical thinking, as a form often held in high regard, can be viewed as a somewhat hollow construct that philosophy has fostered in its own pride. This pride is precisely what leads textbooks on critical thinking to falter, for they, too, often overlook the application of their own principles upon themselves. Surprisingly, not a single standard textbook on Critical Thinking poses the fundamental question: What, indeed, is critical about critical thinking itself?

Yet, considering that even flat-earthers lay claim to possessing the tool of critical thinking, it becomes increasingly necessary to explore its potential side effects. Upon examination, we might discover that the relentless questioning often doesn’t engender creation; rather, its primary function frequently appears to be the elevation of the questioner. Furthermore, we ought to consider whether the acid of critical inquiries might inadvertently harm the questioner. Ultimately, the unrelenting onslaught of criticism may even undermine the very reputation of questions themselves.

In that context, it’s rather intriguing to note that a questioner ascended to become one of the most influential figures in the realm of old-white Western thought.

By now, Socrates has been dying for more than 2000 years. His half-death has left a q

By now, Socrates has been dying for more than 2000 years. Over two millennia have passed, and Socrates’ slow descent into a figurative demise has etched a question mark into the annals of Western tradition. Yet, instead of bequeathing us with enduring questions, his legacy has served as the crucible for embittered, acrimonious, and resentful intellects. It wasn’t Socrates who erred; rather, it was many of his disciples who proved unprepared for the consequences of unyielding critique. They were not ready to stand by their own words and principles, choosing instead to wield questions as weapons, aimed squarely at their adversaries.

In the end, what was meant to be a tool for critique metamorphosed into a weapon, particularly in the age of the internet, evolving into a potent instrument of intellectual mass destruction. Whereas Socrates questioned the value of established truths, the unbridled critique devoid of foundation has led us to forsake truth altogether.

Socrates likely recognized that the dialectic of his questioning aimed to elevate one’s perspective to a higher plane. Critique should not solely target external subjects but, concurrently, demand introspection about one’s own position. By this, I do not refer to daredevils riding homemade rockets or individuals who commit heinous acts for misguided ideals.

Socrates was prepared to embrace his own demise so that the practical, living person could be supplanted by the ideal. His willingness to undergo suffering and sacrifice may be seen as an anticipation of Christian narratives. It wasn’t about vanquishing opponents; it was about enduring the agonizing pursuit of truth to allow truth itself to manifest. It was an act of surrendering power.

What about our aging, white Western man in this narrative of sacrifice? His former wife, now wielding truth as a weapon, has successfully launched a trillion-dollar business. She remains resolute in refusing to acknowledge anything positive about their past relationship. Perhaps there’s truth in the notion that a marriage in which your spouse questions every decision can be stifling and filled with what’s often termed “toxicity.”

However, in her solitude, during her own process of detoxification, her relationship with truth has also grown constricted. Faced with the notion that Western thought may have played a sinister role in humanity’s history, she now leans toward rejecting truth altogether rather than allowing him back into their shared space. This stark division reflects a failure to complete her own journey of critical thinking. As a society driven by science, we’ve primarily learned the art of critiquing the other. Perhaps it’s the phantom pain of the missing partner that still harbors residual anger and mistrust.

Science often extols itself as the epitome of rationality and self-discipline. The prevailing belief is that it possesses the capability to rectify its own course. However, isn’t this self-congratulatory self-control reminiscent of the attributes found in autocratic regimes? Science whispers that its authority equates to progress, but reason transcends the domain of a self-assured intellect that asserts mastery over its own domain and dwelling.

Delving deeper into this notion, shouldn’t science embody a more feminine essence? Specifically, an elevated awareness of one’s body as a fluid concept that, akin to giving birth, can transform into something different? However, in the realm of criticism, science has adopted masculine characteristics—a force of dominance. Gender-fluidity might not be a matter of choice, but a force that can overpower us. Gender, at its core, pertains to questions of power and the extent of influence one wields.

As science critiques others and momentarily seizes the moral high ground, the excessive nature of this criticism might lead us to forfeit our connection to the larger whole and to others. In doing so, we risk losing our relationship with the other as an extension of ourselves (Notes on the Dependence of Independence on Dependence).

Nearly every viewpoint that originates from a place of criticism finds itself submerged in the corrosive bath of that very criticism. As the critic grows ‘self-conscious’, believing that external forces can no longer harm their voice, they inadvertently start to lose the self-consciousness required to remain receptive to the pain experienced by those who exist as “the other.”

It is self-consciousness that means to become humble with regard to the presence of the other and that give us back to ourselves in the other (Notes on Socrates’ soul and its inner city).

“We are too weak to discover the truth by reason alone” – St. Augustine (see Note: Reason as Inferential Activity)

Maybe, the recent criticism means that the old-white Western philosopher should be left alone and die because maybe Socrates taught us that philosophy lives by dying. Perhaps the recent wave of criticism suggests that old-white Western philosopher should be left to their own devices, to fade into the annals of time. We might consider the lesson Socrates imparted to us: that philosophy thrives through its willingness to undergo transformation. Philosophy, in essence, exists as the very paradox of sacrifice. It yields to the criticism, born from pain and often buried beneath layers of anger. It surrenders, it withers away, only to be reborn in fresh incarnations. When it relinquishes resistance, it can truly die, and through that very death, philosophy continues to live. In this vein, we might proclaim: Philosophy is dead, long live philosophy!

Why this Blog?

This blog primarily concerns the demise of old-white Western philosophy rather than its defense. However, my philosophy doesn’t align with the “no” philosophy, which often gets lost in hollow criticism and relies on external content for critique. Instead, I embrace a philosophy of “yes” – a form of critique delivered with a smile, capable of transcending pain through humor. In many ways, it resonates with Hegelian thought. In Hegel’s perspective, the wise acknowledge the circumstances of their historical moment but occupy a reflective position, generating concepts for the future.

As Sloterdijk suggests, a philosophy of “yes” signifies the capacity to say “yes” to the “no.” In this context, it means embracing the joy associated with the death of philosophy, releasing it from the torment of power and resistance. This philosophy severs ties with the negative disposition of critical thinkers who perpetually monitor their doomsday clocks and lament the state of our existence. It is a philosophy that rejects embracing misery.

What else should we want than that the people in their power of criticism step aside and allow us to see the sun? So if somebody asked me about what is my philosophy, I would therefore answer: I already had to give up too many claims in my life (notes on the undead philosophy). Truth is not a matter of defense, but a matter of unarmed seeing. Is this academic? I am not sure, but after my PhD-defense I feel powerless. Is philosophy useful? I ask myself this question almost everyday. Is philosophy finally dead? You tell me, but keep in mind Epictetus recommends:

“Don’t explain your philosophy. Embody it.”

― Epictetus

Why should you follow this Blog?

Socrates knew that he did not know and in this sense he also recognized the empty shell of institutional education. The following quote is probably also misattributed to him but it captures his attitude toward the question of education: “I cannot teach anybody anything. I can only make them think”.

Why should you follow a blog that does not promise you anything; a blog that questions its own usefulness? Well, if you have read up to here, you may know yourself:

Twitter

Instagram

Questions

In general, I follow the idea that questions help us in processing content and learning. For that reason, I will attach in all articles questions that you can answer in the comment section.

- What is the history of philosophy and its current status?

- Why is philosophy dying?

- Is philosophy a “useful” major (what is the quantifiable and what is the unquantifiable perspective on this issue)?

- Why is Critical Thinking in current educational and societal contexts problematic?

- Why is Socrates’ approach superior to standard Critical Thinking?

- What does the sentence “philosophy is dead, long live philosophy” mean?

- What is a possible alternative to the current paradigm of academic philosophy?

- How does a philosophy of “yes” include a philosophy of “no”?

- According to the article, is philosophy useful?

- Why asking questions?

Helpful Links

- For finding valuable quotes in general, Goodreads usually provides a qualitative selection:

- If you seek inspiration, this is a robot that randomly generates them: http://inspirobot.me/

- For reliable information on philosophy, Stanford is usually the best website: https://plato.stanford.edu/contents.html

- A website that lists pro and con-arguments of different questions: https://standardizedtests.procon.org/

- If you need more links, you can also go to my-link-page

OMG endlich